Far From Home

Sitting on a bench under the tile roof of one of the ornately-carved covered walkways connecting buildings I wrote: “I am so stoned today I can hardly write. Stumbling around this ancient town, the Daoist temples, eating a most delicious apple off a street cart, China is everything I expected, absolutely incredible. When I am having trouble finding this place, a lovely girl in a red coat gets off her bicycle and points the way. I walk streets where gardens are spread out from the road, as in the country. I go into a space where bonsai, bits of moss, persimmon trees, ginkgoes, pines have been growing over amazing rocks for centuries, carelessly. A long, even-sounding conversation is going on in the background.”

And yet I did not feel at home in China. In large part the problem was language. But also it had to do with how I felt about the actual physical place. My body would not settle anywhere, kept moving on, feeling a profound discomfort. I knew my genes and immune system had not been adapted to this landscape. China felt like it had an unfamiliar layer of grit on it. The bare dirt in parks was always swept clean, leaving dust on the lower leaves of every tree. This unease, I finally understood, was what homesickness felt like.

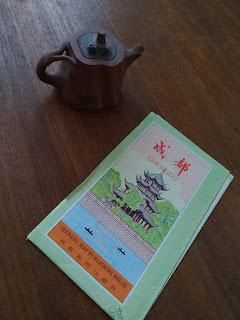

I moved to Hong Kong, but the failure of this plan quickly became obvious. I could not learn Cantonese or the Mandarin my friends spoke in two years, would never understand the jokes. Also, I was ashamed to be part of an English-speaking-only class of foreigners. Before going back to California, however, I decided I should take a trip into China. I chose the town near the Tibetan border, where Du Fu had briefly lived and written poetry.

“In the evening I stop at Five Pine Mountain,

Where the village feels deserted and lonesome.

The peasant families have to work hard.

The woman next door keeps pounding rice in the cold.

My hostess kneels to serve me wild rice,

Moonlight shines on the full white plate.

She makes me feel so unworthy that

I thank her three times and still cannot eat.”

Chinese poetry has always assuaged my love of concrete, sensuous reality, while western literature has felt mired in metaphysics. Li Bai was restless, however, and the complex around Du Fu’s thatched cottage a national shrine. It was a place I could go.

The Daoist temples were laid out in a line. Inside, in front of statues of the three Pure Ones were altars with bowls of nuts and mandarin oranges on them, and a place to burn incense. I knew that these manifestations were a front for a religion whose most authentic representations could only be found deep in the mountains. Along the edge, a monk in a Chinese jacket, trousers and top knot, watered the nandina. I didn’t stop at the inviting open-air tea house as I didn’t know how to ask for tea. I was learning a lot from China, much of it about myself.

Many years before, when I made the move to California from my Midwestern roots, I often longed to go home. California’s dry golden hills had not yet replaced in my heart the woods and spacious skies I was used to. I told myself it would take seven years, the time it took for every cell in the body to replace itself, to become comfortable. In fact the fifth and sixth years were the toughest, but by then there was no question of returning. I was married and settled.

Many people live their lives in an exterior landscape to which their interior life cannot acclimate. Syrian refugees in Canada, Hmong in Minnesota, Antonia’s father in Willa Cather’s My Antonia. What profound sacrifices people make so that their children can avoid poverty or violence, have the educations and lives not available in the countries the families have come from. Until we leave them, we do not realize with what firm bonds our poor little bodies are attached to the places they first knew.

By the time I arrived in Hong Kong, the first leg of my anticipated journey, home was California. I was a desert rat, never happier than when spread out in the sun on a beach or on an island, my head covered to protect my eyes and thin scalp. I knew only that I was a writer and that I was free. Or thought I was. When I applied for a visa to go into China (Hong Kong was still an independent British protectorate), I listed my occupation as “poet/writer.” The person helping me shook his head. “Poet” was okay under the current circumstances (a little more than a year since the crackdown at Tiananmen Square), but not “writer”!

But, of course, it wasn’t just language and landscape which drove me to realize that I couldn’t stay in Hong Kong and wasn’t really free. The toll of divorce is complex and difficult. I wasn’t emotionally resilient. I missed people, familiarity. Friends had generously provided me with their resources in Hong Kong, but I tried not to rely on them too heavily. I was desperate about the mail and when my sister, on a trip to India, had a layover at the Hong Kong airport, I tried to meet with her. She was held in a transit lounge and wasn’t allowed out, nor I in, though I waited outside. I was finally able to send her a note.

After two months in Hong Kong, and having difficulties in pinning down a job, I reversed course and returned home to California. Upon landing, I was thrilled to pick up my luggage and board a familiar Supershuttle. My sister welcomed me and asked if I would watch her children the next day. It was Veterans Day and there was no school, but both she and her husband would be working.

So, a day after returning I went to a lake in Golden Gate park with seven-year-old Peter and five-year-old Tara, my favorite companions. We called it “blackberry lake” because of the thick, runaway brambles where we could still find, at that late date, a few blackberries.

I was ecstatic. While the kids played, I lay back on the clean long red needles dropped from the pine trees above and looked up at the blue sky. The air smelled pungent and the sun glinted on leaves and needles. My muscles drank in the dry warmth. Seagulls chased the other birds away from the breadcrumbs Tara scattered. Everything in me relaxed. This was where I belonged.

Comments

Post a Comment