The Inner Landscape

|

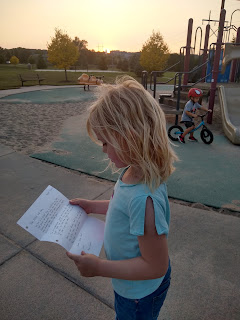

| Abbie Reading a Letter |

The railroad tracks ran along the wide main street on the far side, beside them the train depot and two giant grain elevators. My sisters and I had spent many hours counting railroad cars. No trains that day, but I did see the depot man hang the mail bag on a hook for the next train to snag, throwing out a bag of mail for us as it sped past.

I kept going to the store where Mr. Knudsvig greeted me. His was partly a dry goods store and he sometimes ordered things for us, such as the newly illustrated editions of Laura Ingalls Wilder’s books as they came out. I got my bread, milk and eggs and showed them to Mr. Knudsvig, who wrote down on a little green pad the prices he would add to the bill my Dad paid at the end of the month. He put the yellow paper copy in my bag to take home.

Walking home, I rushed past the gas station. More slowly I went down the sidewalks in front of the houses on the last block. I didn’t know anyone who lived there, but I peered at the windows to see what I could see. I was excited by the smell of the air, the snow on my tongue which tasted a little like dirt, the winter birds. In my head I was making up the words for the story I would tell Mother about the trip.

The question is, why do words crowd my inner landscape, instead of math or music or images. A barren, monochromatic winter landscape, across which one could see for miles, excited me. The small changes in weather, trains, birds, people made up my story. When I got home, bursting, Mother was washing dishes, a captive audience. But she didn’t want to listen. It had happened often enough that she was wary of me. She acted as if I was presumptuous, making myself important. Gently she brushed me off. And perhaps that is as important as my need to speak. The long inner monologue began.

Though she didn’t want to listen, Mother encouraged us in other ways. Our house was full of books and glossy magazines: women’s magazines from which I cut paper dolls and house plans, the National Geographic with its exotic lands and peoples, and Life, which brought a wealth of photographs and news about the world into our isolated house. We were given piano lessons. I imagine the conversations between my parents, discussing how to spend their small income. Mother plumped for culture, Dad for popular science.

But it is probably this first hint at being thwarted that made my brain double down on words. There might be genetics involved. All of the descendants of my Danish grandfather were gifted either artistically or as writers. Both my father and mother were excellent writers and storytellers, though Mother always insisted she “had nothing to say.”

Playing Authors, a favorite card game with five English and six American writers each with four books in a suit, there was only one woman: Louisa May Alcott. I read her books, some over and over. Eight Cousins, Rose in Bloom. Lovely, placid books. When I read them now, I can recall whole sentences.

The first thing I wrote that remains is a set of notebooks begun as letters to Anne Frank, whose diary I had just finished. When I began them I was almost 15 and feeling needy. Anne would understand, I thought. I was already splitting myself into characters, the outgoing Kathy, who wanted to be popular and pretty, and the quieter Kym, who wanted to be cultured and was reading Chinese poets.

Thus, the kind of intimacy I craved grew up between myself and three women writers: Laura Ingalls Wilder, Louisa May Alcott and Anne Frank. From their books I learned more than I could about some of my sisters, who sat down to meals with me every day. The circumstances of these writers and their thoughts were evident in their books. Words not only haunted my inner life. I also thought that in order to share this intimacy, I must become a writer.

It did not go well at first. At college I was accepted into the only creative writing seminar. Somewhat experimental, it was taught by Eugene Olson, after the fashion he had learned at the University of Iowa: participants wrote fiction and passed it around among the 15 of us. Aside from completing assignments, Olson gave us freedom to write what we wanted and required only that comments we made on each other’s work be positive and productive. Some of the stories I wrote got into College Chips, the campus newspaper. I remember one comment on a story, a quote from e. e. cummings: “nobody but the rain has such small hands.”

Nevertheless, Olson’s example as a published writer of true crime and paranormal fiction inspired no confidence whatsoever. Neither did my foray into advanced English scholarship. In my last summer at school I audited a seminar in which the English faculty and students read William Empson’s Seven Types of Ambiguity. An exemplar of the “new criticism” coming out of Cambridge University, the thick volume describes the way authors, generally poets, allow alternative readings showing conflicts in themselves and complexity in their work. I didn’t try to read the book myself and in fact I couldn’t understand the discussion of it! I sat looking at the people in the group, describing their relationships to myself, as if they were characters.

As the oldest of eight kids, I needed a way to make a living. I applied for a fellowship in library science at the University of Michigan. As soon as I got there, with money to spend, I bought a typewriter. “But you’re not going to have anything to write about until you’re 40,” I told myself. It was 1967. I settled down and began acquiring the experience I needed.

Journaling never quit, however. I wrote constantly. Twice I threw out pounds of them, ashamed of the emotional stew they represented. Finally, openly declaring myself a writer, I determined that the journals must not contain anything I couldn’t speak about freely. I now have forty years worth, which are either cryptic enough to keep, or else I have grown less embarrassed.

I did go to writers’ conferences and workshops, realizing in the end that they had no effect on my writing. And I have resisted advice about publishing, refusing to let the market drive my work. It may come around, or it may not. I do not see the world in romantic terms riddled with the tragedies and triumphs of heroes and heroines. And perhaps this is also what my mother’s resistance to endless confessions of feelings was trying to show me.

We may dwell on either side of the fractal edge at which our inner self meets the world. The imagination can thus be applied to dreams and mystic inner worlds or to sensual, concrete reality. The outer world is a place in which people live as part of a vast pageant of happenings. Our emotions are the weather. Beauty is everywhere. Submerged in our own dramas, we may not see it. But if we step out for a moment, it engulfs us, suffusing our inner world in light.

You can imagine my delight at coming upon, near the Art Institute in San Francisco one summer, a thin line of words embedded in the sidewalk. Cut from a long narrative typewritten on white paper, the words proceeded up the block and around the corner. I am not sure how the artist had affixed them to the sidewalk so they were not obscured by dirt and footsteps. I just loved the idea of them trailing up the broken sidewalk beside little plants springing up through the cracks.

Comments

Post a Comment