A Window into the Sacred

At the market I quickly ran into Emiko, thin, dark and animated. She was looking for me, wanted to share the apple butterscotch pastry she had bought from the stellar Della Fattoria bakery stall. Emiko was one of my early tai chi teachers. She lived far enough away that she had to drive to the Marin County farmers’ market. We usually didn’t call each other to agree to meet. We simply looked for each other, counting on our shared passion for the market.

Two rows of vendors, with an espresso and coffee vendor right next to the bakery stall at one end, prepared food stalls, rotisserie chicken and taco trucks at the other. People came from the nearby Civic Center for lunch all year round. I knew the area well. On one end a marsh and a canal veered off toward the San Francisco Bay. The market was the best place to buy organic vegetables direct from Full Belly Farms and other places. We had our favorites. When Emiko and I discovered the small, crisp succulent Persian cucumbers an older woman had begun to sell, we always stopped there first to make certain she didn't run out.

We were especially friends with the Korean mushroom lady. She had very fresh mushrooms of all varieties: cremini, shiitake, chanterelles, maitake; even morels in season. When her helper, Sukhui, told Emiko she wanted to learn tai chi, Emiko recruited me, since Sukhui lived nearby. I worked with Sukhui, a good student, for many years until I moved away.

This particular morning, Emiko bought a cappuccino and I found us a rickety little painted table with similar chairs. Flakey pastry, sunshine, springtime. The market had been full of citrus fruit, oranges, mandarins, pomelos. But vegetables, especially greens, were plentiful too.

Emiko shared an experience that happened when her Iyengar yoga teacher, the renowned Judith Laseter, said to the class: “Pay attention to everything in daily life. All of it is a window into the sacred.” It was something I agreed with implicitly. Emiko said, "I usually slam the door on my garden shed. But this time, I shut it very quietly. A great silence came, which hit me almost physically.”

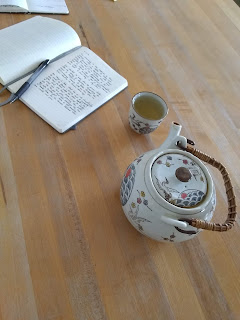

I explained that I had been trying to hold my teacup (the small handle-less Chinese-style cup) with both hands. “Shunryu Suzuki, whose biography I have been reading, always did this. It feels very different. A complete circle of the body, rather than the open, incomplete gesture we use in the West.” On warm, wet mornings, while waiting for people to come down to breakfast, I often stood out on my back deck, drinking tea in the sunshine and listening.

Stonehouse (1272-1352 AD), who lived on Red Curtain mountain, near Huzhou, in seclusion for most of his last forty years, wrote, “People say everyday-mind isn't buddha, but buddha’s nothing else” [#137 in The Mountain Poems of Stonehouse, translated by Red Pine]. Stonehouse was hard-working, growing his own millet, collecting wild greens and firewood, patching his ragged robe. But he also spent long days in contemplation. When someone brought him a brush and writing paper, he sat down and dashed off almost 200 poems, until he had run out of paper.

But what is the sacred? Why do we have to be continually reminded to live in the numinous, the sacred, the transcendent? Jordan Peterson, in his book 12 Rules for Life, tells us that when we can’t think our way out of our problems, we must try noticing. When we merely think, we are impeded by our personalities, our biases. We shut off possibilities we might see if we opened ourselves to them. Our human cerebral cortex is very powerful and arrogant in its certainty of its superiority. The humility of paying attention to the everyday is one way to get it to back down!

I remember exactly when I decided that the split between sacred and profane was a trick. “It’s either all sacred or all profane,” I thought to myself, sitting by an older visiting aunt in a church service she had wished to attend. “I don’t care which.” I haven’t backed down from that insight of forty years ago. The world in its complexity, explainable or not, is one thing. Our inner experience of it can be similarly whole, though it may be difficult to sustain the feeling. It is perhaps just too scary.

When teaching cinematography, Don used to have at least one class in which he took students out into the street (with cameras) and asked them to spend some time noticing what was around them, and film it. Noticing comes more from the right hemisphere of the brain, the visual, non-verbal side. Developing this side of the brain can counter the hyper-active critical and language-oriented left hemisphere.

Lately we’ve been watching videos the lovely Li Ziqi posts of the artful life she lives in the Chinese countryside. Having learned much of the old ways from her grandparents, Li Ziqi plants and harvests rice, grows fruit and produce as well as collecting it from the woods around her house. Preserving and pickling fruit, peppers and vegetables she has hundreds of ways of using them. She buys meat from neighbors and cooks it, stoking a fire under huge ceramic woks. When she washes vegetables, we hear the water running; when she plucks a fruit, we hear it; branches swish beside her. And then we see her sit down and share food with her grandmother. The wholeness of this life, shown without much talk, is inspiring. Several of us, after watching these videos, find ourselves noticing our own hands as we stir the pots on the stove or the sounds of the water as we pour it into the teapot.

Should I be surprised that so much of this particular wisdom comes from somewhere west of where I live? No. For all of the more than 50 years in which I have lived in California, I have felt myself perfectly positioned between East and West. I am thrilled to inherit a strongly individualist and democratic tradition, developed in Northern Europe and Greece. But I have also made Chinese poets my teachers, for their lack of ideology and understanding of how humans are part of nature and live by its laws.

Alain de Botton asks the question, aimed at the West, “Why is an ordinary life not good enough any more?” He thinks it poisons our thinking to require fame or lots of money in order to get the love and honor we deservedly want. “Most of us are going to live an ordinary life,” he says. The “snake in the grass” tripping up our expectations is the requirement to be extraordinary.

As I write, we are beginning to come out of a year-long world-wide bout with a deadly virus, COVID-19. It has up-ended most people’s habits, education, travel and economic futures. Everyone has had to find ways to cope. My niece, Jessica, upon being able to take her son to join other parents with their children to make forts in the recently-downed trees after a storm, said: “What used to be normal is now precious.” Perhaps, once we all start going in many directions again, we will look back on this time as helpful to renewing family ties and our enjoyment of everyday pleasures. It’s an ill wind, as they say, that blows no good.

Update and corollary: Astra Taylor notes here that "Everyday life is the primary terrain of social change."

Comments

Post a Comment