Dignity

Dissolving in a heap of giggles in front of a mirror at the new Southdale Mall in Minneapolis, I got my sisters and my poor, beleaguered Mother going too. I can only think it was due to the incongruity of the situation. We were trying on dresses, a gift to each of us from my aunt at Christmas, the only time all year we could count on a new store-bought dress. But I had never been to a shopping mall, never seen myself in a full-length mirror. Was that gawky, spotty-faced 15-year-old with the limp hair, me? I didn’t look anything like the girls in the Seventeen magazine.

Was my sense of absurdity a hint of my future? My family had come to stay with our cousins at a beautiful Victorian house in St. Paul at Thanksgiving. Mother thought it would be fun to do our shopping in person, instead of through the Sears Catalog as we usually did. She had six little girls to find dresses for, plus a three-year-old boy. I am sure my brother hung out with Dad during this comical ordeal in the dressing room.

I remember what I ended up choosing, a rose-colored skirt with a white blouse, embroidered with small roses on the collar. When I ask my sisters what they chose, none of them remember being pleased with their Christmas dresses, feeling that they hadn’t much choice. And who can blame our poor mother! I think we only did this in-person shopping once.

The Christmas dresses were an unfailing tradition, however, the generosity of an older sister to her younger one. My aunt had no children, but her brothers and sister had lots! She was a grade school principal, having begun teaching at a young age to support her mother when her father died. We learned from her example how families took care of each other in adversity, but also about dignity.

Looking back, it seems to me that all of our parents and grandparents had a sense of dignity with which our peripatetic lives cannot compete. What composed this dignity? What made it up? Dignity is a “formal reserve or seriousness of manner,” but also it is a feeling of value, of personal worth. Is dignity to be valued? I think it must include a kind of contentment with one’s circumstances and what one has achieved in life.

My mother’s mother married a pastor from Denmark who came to America as a missionary. The fact of being in the Lord’s service, and employed by the Danish Crown carried an aristocratic sense of dignity that my grandmother took with her until her death. She also handed it down to her children. Equally, in a different way, my father’s mother derived her sense of dignity from her excellent housekeeping. She had been a hired girl, but she married a forward-thinking carpenter and mechanic and rarely left her southern Minnesota home.

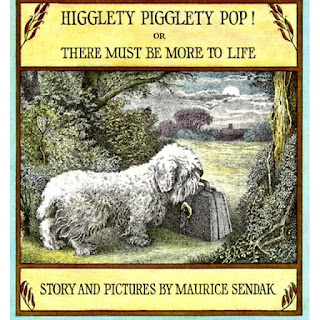

It seems to me that my generation threw out dignity in favor of openness to all kinds of experience, as well as freedom to move in circles different from those we were born into. We were afraid of the stiff beliefs and static rituals, (even the furniture!), which bound our parents in place. “Higgelty, piggelty pop,” we said. “There must be more to life [a Maurice Sendak story, published 1967].”

We lived in the famous “generation gap” which bridged an older and a younger culture. We are still recovering! Many of us are still trying to assign value to lives which haven’t stopped moving. Where are we going? What have we done?

There is an evolutionary value to living on that fractal edge between chaos and order, though it may not be very comfortable. It was said that if you weren’t a radical when young, you had no heart; but if you weren’t conservative when you got older, you had no head. My generation, known as the baby boom, is older now, and I am wondering in what to constitute our dignity.

In a lighter sense, every person walking down the street has human dignity. Animals have their own, as dogs, birds and certainly cats! Wild animals stun us with their amazing presence, so full of their own self-ness. It is what we want for each other, for each person to connect their inner dignity with the self that moves in the world.

The philosopher Alain de Botton says that “The more dignity is widely and freely available in a society, the less people want to be famous.” In other words, where ordinary life provides dignity and comfort, people are content with what they have done. (More Alain de Botton on success here.) The generations of my parents and grandparents lived through the world-wide cataclysms of the Great Depression and World War II. Everyone contributed to the turn of those tides, finding their inner dignity and worth.

If my generation tossed everything in the air and demanded it justify itself, we have made a different world from the one we came into. Those of us who lived there thought that the multi-cultural effervescence of San Francisco in the 1970’s and 1980’s could not be beat. Search engines and databases, cheap communication, global awareness and trade have all contributed to increased complexity, climate change and discrepancies between rich and poor. But humans haven’t changed very much and we all put our Levi’s on one leg at a time.

Gary Snyder, in an essay from The Practice of the Wild, recounts this exchange: “Florence Edenshaw, a contemporary Haida woman who has lived a long life of work and family, was asked by the young woman anthropologist who interviewed her and was impressed by her coherence, presence and dignity, ‘What can I do for self-respect?’ Mrs. Edenshaw said, ‘Dress up and stay home.’ The ‘home,’ of course, is as large as you make it.”

It is time for all of us to consider our dignity. We can take a good look at the older people around us and see what constitutes dignity or the lack of it. We are grateful for the incredible gift of a human life. Defining our dignity and living in it shows our appreciation.

Comments

Post a Comment